Explore the collection

Showing 273 items in the collection

273 items

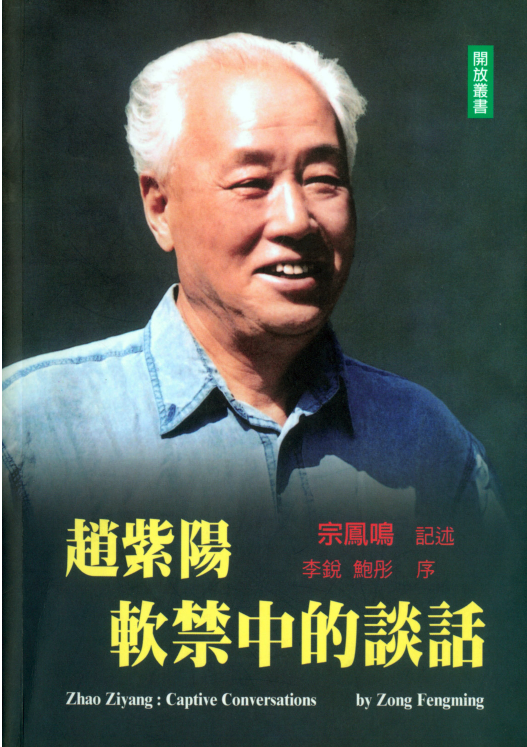

Book

Zhao Ziyang’s Conversations Under House Arrest

In January 2007, Hong Kong Open Press published the book "Conversations of Zhao Ziyang under House Arrest". It was narrated by Zong Fengming and prefaced by Li Rui and Bao Tong. The narrator, Zong Fengming, is an old comrade of Zhao Ziyang. He retired from Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 1990. From July 10, 1991 to October 24, 2004, using the name of a qigong master, Zong Fengming visited Fuqiang, who was under house arrest in Beijing. Zhao Ziyang, who lives at No. 6 Hutong, had hundreds of confidential conversations with Zhao Ziyang. This book is a rich account of these intimate conversations. Zhao Ziyang talked about the power struggle and policy differences within the top leadership of the CCP, his relationship with Hu Yaobang, his evaluation of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, his criticism of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, Sino-US relations, the Soviet Union issue and Taiwan issues. He also conducted in-depth reflections on the history of the Communist Party.

Book

Zhu Xueqin Anthology

A collection of essays by Zhu Xueqin, a Chinese liberal intellectual. He has faced and criticizes various problems in China from a liberal point of view. Most of Zhu Xueqin's books were later banned.

图书

An Eyewitness Account of 1989 by a PLA Soldier

<i>An Eyewitness Account of 1989 by a PLA Soldier</i> is written by Cai Zheng. In 1989, Cai Zheng was serving in the People's Liberation Army Air Force in Beijing. On June 5th, near Tiananmen Square, he was arrested and severely beaten by martial law troops after he protested against the massacre. He was then detained for over eight months at the Beijing Xicheng Public Security Bureau and by his own military unit, enduring torture. Afterward, he was sent back to his hometown of Hong'an in Hubei province.

The book offers a detailed account of Cai Zheng's experiences as a soldier during the June Fourth crackdown and his subsequent struggles for survival in his hometown. It provides valuable insights for researchers seeking to understand China's social and historical environment before and after the events in 1989.

Published in 2009 by Mirror Books, this memoir is held in various public libraries in Hong Kong and by many university libraries worldwide. The book has also been subject to pirated editions within China.

图书

Summer of 1989: We Were in Beijing

<i>Summer of 1989: We Were in Beijing...</i> compiles numerous firsthand accounts detailing the experiences of students from The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) who were in Beijing and Shanghai during the 1989 democracy movement. A total of thirty CUHK students traveled from Hong Kong to Beijing to show their support.

The Hong Kong students interacted with student movement leaders at the time, attended meetings of the Beijing Students Autonomous Federation, participated in organizing efforts, and even edited a publication called <i>News Express</i>. They also set up a supply station of provisions in Tiananmen Square and supported the establishment of "Tiananmen Democracy University." A number of these students personally witnessed the June Fourth crackdown.

On the eve of the crackdown, official broadcasts in the square sternly criticized students from “a certain Hong Kong university” for forming illegal organizations. <i>People's Daily</i> directly named and criticized the Chinese University of Hong Kong Student Union on June 15th, after the crackdown occurred.

The Chinese University of Hong Kong Student Union published this book in 2014, stating its purpose as safeguarding history and combating official brainwashing. It also hopes that readers will understand the Tiananmen democracy movement from the perspective of Hong Kong students and to explore the role of CUHK and Hong Kong academia in this movement.

电影及视频

Global Feminisms Project: China Interviews

The Global Feminisms Project, hosted by the University of Michigan, archives oral history interviews with individuals who identify themselves as working on behalf of issues related to women and gender in different national contexts. The goal of the project is to encourage teachers and researchers to study issues related to the many forms of feminist or women’s movement activism in general, as well as activism on behalf of particular issues.

Beyond that, this project is also a useful resource for general readers who are interested in learning more about the history of feminist movements around the world. Interviewees describe their lives, their views, and their activism in considerable detail. The project offers the unedited interviews as primary sources for understanding the history of activism in all its complexity and variation.

The project covers 14 countries, including China, with each having a dedicated site. According to introductions by Wang Zheng, then a professor at University of Michigan’s Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the China Interviews took place in two phases.

In the first, the interviews illustrate the multi-dimensional development of feminist practices in China’s transformation from a socialist state economy to a capitalist market economy from the mid-1980s, when spontaneous women’s activism emerged. Situating such development in the context of both global capitalism and global feminisms, especially in the context of the Fourth UN Conference on Women (FWCW) when Chinese feminists came into direct contact with global feminisms, the interviews, conducted in the early 2000s, explore the cultural, social, and political meanings of Chinese feminist practices. They illustrate how official, non-official, domestic, and overseas Chinese women activists expressed diverse visions of gender equality, even engaging in struggles over the very word “gender.”

These interviews reflect the scope and complexity of the contemporary Chinese women’s movement. Feminist activists include women leaders from diverse groups, such as Ge Youli, who was involved as a young leader in various urban based organizational activities funded by international donors to disseminate feminist ideas; Zhang Lixi, Vice President of the Chinese Women’s College that affiliates with the All-China Women’s Federation, who has promoted women’s studies in her college; Ai Xiaoming, prominent feminist scholar and activist; and Gao Xiaoxian, who holds an official position in the Shaanxi Women’s Federation while creating several women’s organizations outside the official system to engage in legal services for women, anti-domestic violence movements, and issues of gender and development.

In the second phase, five interviews of a younger cohort of Chinese feminists record the rapidly contracted public space for NGO activism in China since the second decade following the FWCW and severe surveillance by the state over feminist activities initiated by autonomous feminist groups and individuals. They also provide powerful testimonies to tremendous creativity, perseverance and courage demonstrated by young feminists who in many cases are making a precarious living in the private sector without much resource for their feminist activism.

<a href=”https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/globalfeminisms/interviews/china/”>The China site</a> provides videos and transcripts of the interviews (both in Chinese and English). In addition to the interviews, the archive also provides maps, statistics, a timeline, podcasts and other resources to assist understanding of the context in which the activists carried out their work.

图书

The Truth about Liu Wencai

In the mid-20th century, Liu Wencai, a large landowner in Sichuan Province, spent almost all of his family's wealth in his later years on promoting education, bridge construction and road building, and was known as a great benefactor in the region. However, during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, he was portrayed as an archetype of evil landlords in the 3,000-year history of feudalism in China.

As the controller of great wealth in southern Sichuan during the Republic of China period, Liu Wencai did accumulate a huge fortune from plunder in his early years, but in his later years he invested most of it in public welfare. He financed and presided over the construction of a highway, as well as the Wanchengyan irrigation system, benefiting hundreds of thousands of farmers. He also spent almost all of his family's wealth to found the Wencai Middle School (today's Anren Middle School), which at the time was known as Sichuan's best privately-run school. In the memories of the local people, Liu Wencai collected less land rent than what was collected by the government after 1949. He was praised for providing financial assistance to poor families during special days and festivals, and for mediating civil disputes in a fair manner.

These facts were erased under the ultra-leftist propaganda. The authorities even fabricated the story of Liu Wencai keeping farmers in a dungeon filled with water, as well as making sculptures depicting how Liu Wencai was exploiting farmers, in order to incite hatred against him. This made Liu Wencai one of the most famous evil landlords in China.

Film and Video

Beijing's Petition Village

In China, individuals can complain to higher authorities about corrupt government processes or officials through the petition system. The form of extrajudicial action, also known as "Letters and Visits" (from the Chinese xinfang and shangfang), dates back to the imperial era. If people believe that a judicial case was concluded not in accordance with law or that local government officials illegally violated his rights, they can bring it to authorities in a more elevated level of government for hearing, re-decide it and punish the lower level authorities. Every level and office in the Chinese government has a bureau of “Letters and Visits.” What sets China’s petitioning system apart is that it is a formal procedure—and as Zhao Liang's documentary shows, the system is largely a failure.

A residential area near Beijing South Railway Station was once home to tens of thousands of residents from all over the country. Known as “Petition Village,” its bungalows and shacks were demolished by authorities several times, but many petitioners still clung to the land in search of a clear future. _Beijing Petition Village_ portrays the village in the midst of this upheaval, focusing on the thousands of civilians who travel from the provinces to lodge their complaints in person with the highest petitioning body, the State Bureau of Letters and Visits Calls in the province, only to repeatedly get the brush-off by state officials. Ultimately, in 2007, Petition Village was demolished for good.

The film went on to win the Halekulani Golden Orchid Award for Best Documentary Film at the 29th Hawaii International Film Festival, and a Humanitarian Award for Documentaries at the 34th Hong Kong Film Awards.

图书

A Chronicle of Heroes in Quelling the Turmoil

<i>A Chronicle of Heroes in Quelling the Turmoil—A Collection of Reports on the Deeds of Heroes and Models in Suppressing the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion in Beijing</i> was published by Guangming Daily Publishing House in September 1989. As one of the Chinese Communist Party's official propaganda projects after the suppression of June Fourth, this book collected speeches from a nationwide speaking tour organized by the authorities after the suppression to publicize the "great achievements in quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion." It is one of the texts for studying June Fourth from the official perspective.

图书

One Day Under Martial Law

<i>One Day Under Martial Law</i> was edited by the Cultural Department of the General Political Department of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA), and published and distributed by the PLA Literature and Art Publishing House in October 1989.

The book is divided into two volumes and collects a total of 190 signed articles. Apart from a few police officers from the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau at the time, almost all the authors were soldiers from the PLA martial law troops.

This book is a valuable resource provided by the martial law troops, a special group of witnesses to the June Fourth Tiananmen Incident. The book is a valuable source of information for researchers seeking information on the troops that participated in the June 4th massacre.

This book was also a primary reference for scholar Wu Renhua when he wrote the book <i>The Martial Law Troops in the June Fourth Incident</i>. As an officially organized piece of propaganda material, the book's original intent was to applaud the troops and individual officers and soldiers for what the government described as "quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion." However, because it revealed too much true information, the book was banned shortly after publication. In 1990, the publisher reissued what it called a "selected edition" of the book, which removed over a hundred articles, retaining only 80 signed articles, and the total word count of the book was reduced by more than half. The Archives has collected the original two volumes of <i>One Day Under Martial Law</i>, as well as the “selected edition" that was published after being censored.

图书

The True Face of Fang Lizhi

<i>The True Face of Fang Lizhi</i> was edited by the General Office of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Communist Party of China and published by Law Press in July 1989.

Fang Lizhi was one of Beijing's most prominent intellectuals during the 1989 Tiananmen Square Democracy Movement. An astrophysicist, he was labeled a "rightist" in his earlier years. Starting in the autumn of 1988, he actively participated in political study groups at Beijing's universities and gave interviews to foreign media, openly criticizing the Chinese Communist Party's Four Cardinal Principles, which called for upholding socialism and the Communist Party rule. His views resonated with students in Beijing at the time.

On January 6, 1989, he penned an open letter to then-Central Military Commission Chairman Deng Xiaoping, suggesting that democracy activists like Wei Jingsheng be released that year for the National Day celebrations. In February 1989, Fang Lizhi wrote "China's Hope and Disappointment," which Wang Dan and others posted as a big-character poster at Peking University. In June 1989, the CCP authorities issued an arrest warrant for Fang Lizhi on charges of "counter-revolutionary propaganda and incitement." Fang subsequently sought refuge in the U.S. Embassy and later sought exile in the United States.

This book serves as a propaganda tool for the Chinese Communist Party, compiling Fang Lizhi's what the book called "reactionary statements" where he "opposed the Four Cardinal Principles and advocated bourgeois liberalization." It also gathers articles from Chinese Communist Party newspapers that criticize Fang Lizhi for "inciting and organizing the June Fourth riots." From an official government perspective, the book offers insights into Fang Lizhi's ideas and sheds light on China's social and political thought environment before and after June Fourth.

Book

The Falun Gong Phenomenon

This book is a collection of several long articles and commentaries by Hu Ping on Falun Gong and the persecution and repression against Falun Gong practitioners. From an independent perspective, this book responds to a series of unfair criticisms and stigmatization of Falun Gong by the Chinese authorities and the public, calling on society to fight for the basic rights of Falun Gong practitioners who have been persecuted.

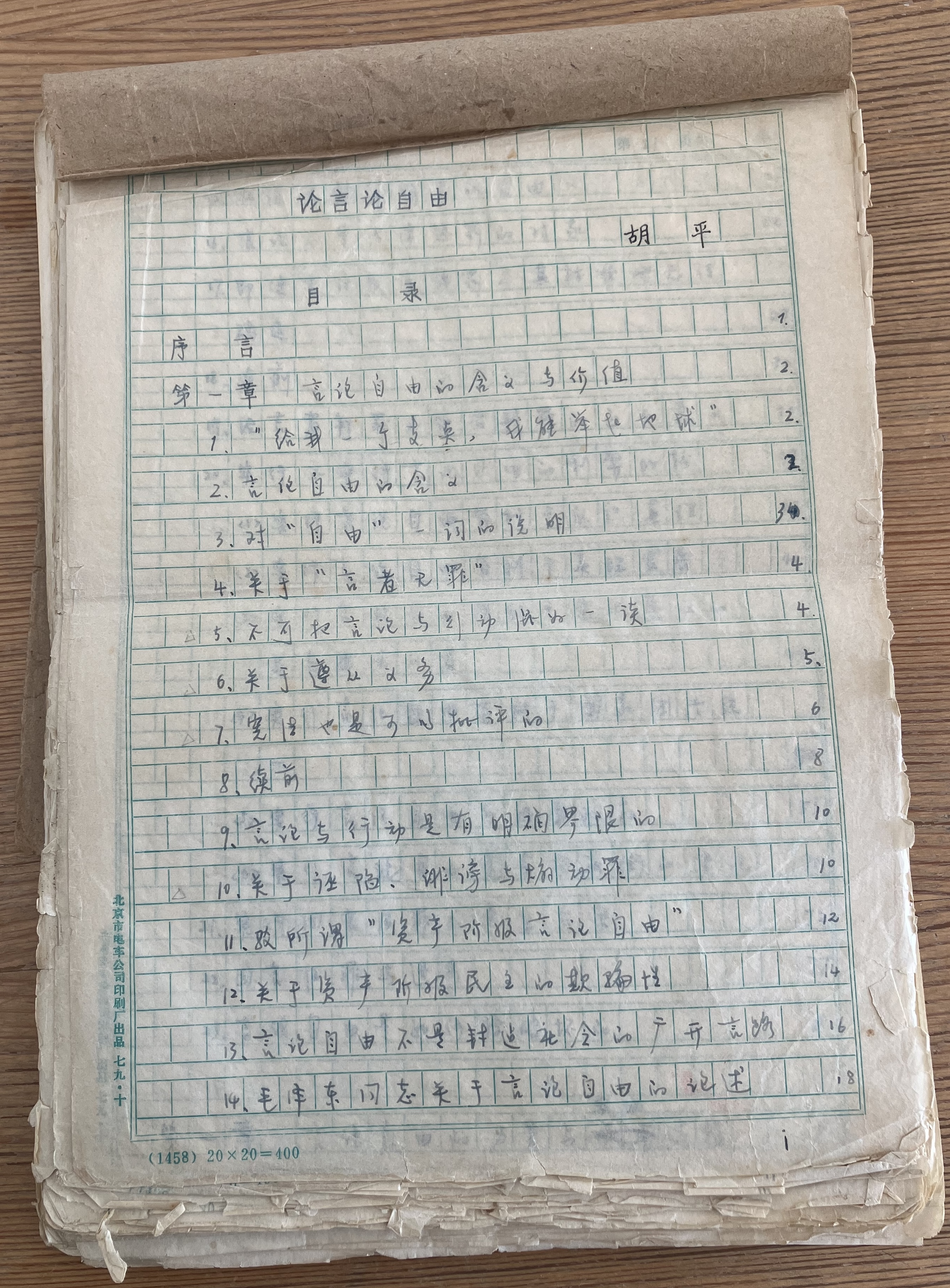

Book

On Freedom of Speech

“On Freedom of Speech” is a treatise by Hu Ping. It was first published in 1979. A revised version was published in 1980, when Hu ran for local elections at Peking University. The treatise was later published in Hong Kong in 1981 and again in a Chinese journal in 1986. Multiple publishing houses in China made plans to distribute the treatise in book form, but China’s anti-liberalization campaign prevented the books from publishing.

“On Freedom of Speech” explains the significance of freedom of speech, refutes misunderstandings and misinterpretations of freedom of speech, and proposes ways to achieve freedom of speech in China.

This document, provided by the author, also includes the content of the symposium held after the publication of “On Freedom of Speech” in 1986, as well as the preface written by the author in 2009 for the Japanese translation of this treatise.

Film and Video

The Vagina Monologues (Performance at Sun Yat-sen University)

<i>The Vagina Monologues</i> is a pioneering feminist drama created by the American playwright Eva Ensler. In 2003, teachers and students at the Gender Education Forum of Sun Yat-sen University in China adapted the play and added artistic interpretations of Chinese women's gender experience. The adapted play had its first performance at the Guangdong Provincial Art Museum on December 7, 2003. This video is a recording of that performance.