Explore the collection

Showing 186 items in the collection

186 items

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 53): Liang Xiaoyan

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

Film and Video

Working Toward a Civil Society (Episode 54): Pu Zhiqiang

How can China build a true civil society? Independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants since 2010.

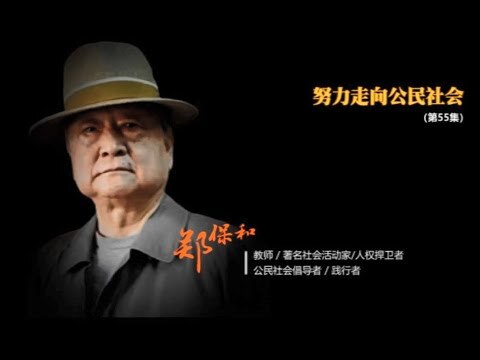

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 55): Zheng Baohe

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 6): He Fang

How can China build a real civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple sat for a series of interviews with scholars and civil society actors.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 7): Guo Yuhua

How can China build a real civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple sat for a series of interviews with scholars and civil society actors.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 8): Xu Youyu

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 9): Zhang Hui

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

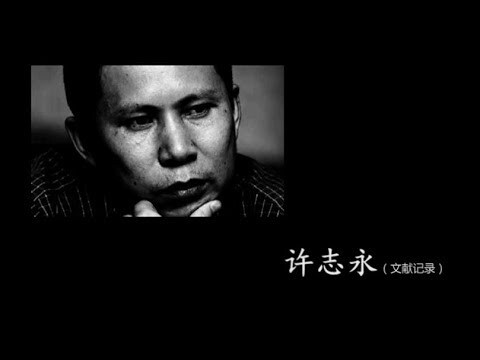

Film and Video

Xu Zhiyong

Chinese human rights activist Dr. Xu Zhiyong, twice imprisoned for his longstanding advocacy of civil society in China, was sentenced to 14 years in prison by the Chinese government in April 2023. The documentary by independent director Lao Hu Miao was filmed over a four-year period, beginning with the seizure of the Public League Legal Research Center, which Xu Zhiyong helped found in 2009, and ending with Xu's first prison sentence in 2014.

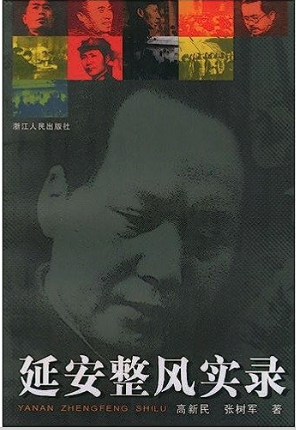

Book

Yan'an Rectification

The Rectification Movement took place in Yan'an, North Shaanxi Province, in the 1940s. This book, written by scholars within the Chinese official system, attempts to chronicle the ins and outs of the Rectification Movement in Yan'an and the base areas, analyzing its causes and the logical development of its results. It is rich in information that is only found here. This book was published by Zhejiang People's Publishing House in 1999.

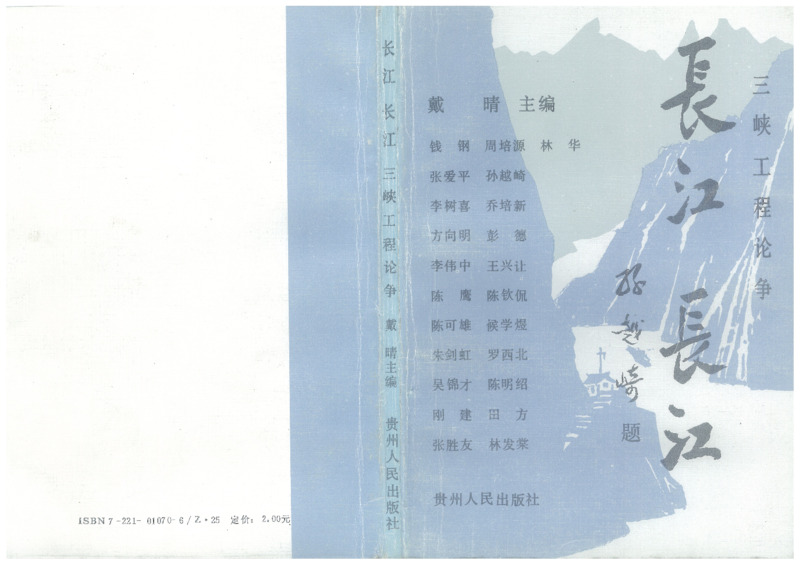

Book

Yangtze Yangtze

In March 1989, the book Yangtze Yangtze was published by the Guizhou People's Publishing House just as the Tiananmen student protests were about to begin in Beijing. The book fed into this intellectual ferment, challenging the technocratic reasons for the Three Gorges Dam, which eventually would dam the Yangtze River in the name of flood control and electrical power generation.

The book was edited by the journalist Dai Qing, the daughter of a well-known Communist Party activist and leader. The book challenged the project's decision-making process, with a broad array of scientists, journalists, and intellectuals arguing that it was not democratic and did not take into account all viewpoints. It was widely read in China and translated into foreign languages.

After the Tiananmen protests were violently suppressed, Dai Qing was arrested and imprisoned for ten months in Qincheng Prison as an organizer of the uprising. Yangtze Yangtze was criticized as “promoting bourgeois liberalization, opposing the Four Fundamental Principles (of party control), and creating public opinion for turmoil and riots.” The book was taken off the shelves and destroyed, with some copies burned. It became the first banned book resulting from the decision-making process of the Three Gorges Project.

The book is banned in China. The English-language edition can be read online at Probe International: https://journal.probeinternational.org/three-gorges-probe/yangtze-yangtze/.

Book

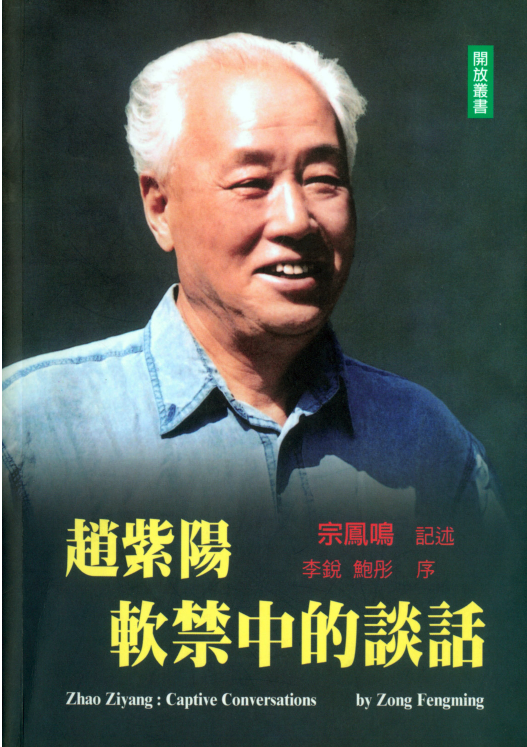

Zhao Ziyang’s Conversations Under House Arrest

In January 2007, Hong Kong Open Press published the book "Conversations of Zhao Ziyang under House Arrest". It was narrated by Zong Fengming and prefaced by Li Rui and Bao Tong. The narrator, Zong Fengming, is an old comrade of Zhao Ziyang. He retired from Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 1990. From July 10, 1991 to October 24, 2004, using the name of a qigong master, Zong Fengming visited Fuqiang, who was under house arrest in Beijing. Zhao Ziyang, who lives at No. 6 Hutong, had hundreds of confidential conversations with Zhao Ziyang. This book is a rich account of these intimate conversations. Zhao Ziyang talked about the power struggle and policy differences within the top leadership of the CCP, his relationship with Hu Yaobang, his evaluation of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, his criticism of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, Sino-US relations, the Soviet Union issue and Taiwan issues. He also conducted in-depth reflections on the history of the Communist Party.

Book

Zhu Xueqin Anthology

A collection of essays by Zhu Xueqin, a Chinese liberal intellectual. He has faced and criticizes various problems in China from a liberal point of view. Most of Zhu Xueqin's books were later banned.

图书

An Eyewitness Account of 1989 by a PLA Soldier

<i>An Eyewitness Account of 1989 by a PLA Soldier</i> is written by Cai Zheng. In 1989, Cai Zheng was serving in the People's Liberation Army Air Force in Beijing. On June 5th, near Tiananmen Square, he was arrested and severely beaten by martial law troops after he protested against the massacre. He was then detained for over eight months at the Beijing Xicheng Public Security Bureau and by his own military unit, enduring torture. Afterward, he was sent back to his hometown of Hong'an in Hubei province.

The book offers a detailed account of Cai Zheng's experiences as a soldier during the June Fourth crackdown and his subsequent struggles for survival in his hometown. It provides valuable insights for researchers seeking to understand China's social and historical environment before and after the events in 1989.

Published in 2009 by Mirror Books, this memoir is held in various public libraries in Hong Kong and by many university libraries worldwide. The book has also been subject to pirated editions within China.

图书

Summer of 1989: We Were in Beijing

<i>Summer of 1989: We Were in Beijing...</i> compiles numerous firsthand accounts detailing the experiences of students from The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) who were in Beijing and Shanghai during the 1989 democracy movement. A total of thirty CUHK students traveled from Hong Kong to Beijing to show their support.

The Hong Kong students interacted with student movement leaders at the time, attended meetings of the Beijing Students Autonomous Federation, participated in organizing efforts, and even edited a publication called <i>News Express</i>. They also set up a supply station of provisions in Tiananmen Square and supported the establishment of "Tiananmen Democracy University." A number of these students personally witnessed the June Fourth crackdown.

On the eve of the crackdown, official broadcasts in the square sternly criticized students from “a certain Hong Kong university” for forming illegal organizations. <i>People's Daily</i> directly named and criticized the Chinese University of Hong Kong Student Union on June 15th, after the crackdown occurred.

The Chinese University of Hong Kong Student Union published this book in 2014, stating its purpose as safeguarding history and combating official brainwashing. It also hopes that readers will understand the Tiananmen democracy movement from the perspective of Hong Kong students and to explore the role of CUHK and Hong Kong academia in this movement.

电影及视频

Global Feminisms Project: China Interviews

The Global Feminisms Project, hosted by the University of Michigan, archives oral history interviews with individuals who identify themselves as working on behalf of issues related to women and gender in different national contexts. The goal of the project is to encourage teachers and researchers to study issues related to the many forms of feminist or women’s movement activism in general, as well as activism on behalf of particular issues.

Beyond that, this project is also a useful resource for general readers who are interested in learning more about the history of feminist movements around the world. Interviewees describe their lives, their views, and their activism in considerable detail. The project offers the unedited interviews as primary sources for understanding the history of activism in all its complexity and variation.

The project covers 14 countries, including China, with each having a dedicated site. According to introductions by Wang Zheng, then a professor at University of Michigan’s Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the China Interviews took place in two phases.

In the first, the interviews illustrate the multi-dimensional development of feminist practices in China’s transformation from a socialist state economy to a capitalist market economy from the mid-1980s, when spontaneous women’s activism emerged. Situating such development in the context of both global capitalism and global feminisms, especially in the context of the Fourth UN Conference on Women (FWCW) when Chinese feminists came into direct contact with global feminisms, the interviews, conducted in the early 2000s, explore the cultural, social, and political meanings of Chinese feminist practices. They illustrate how official, non-official, domestic, and overseas Chinese women activists expressed diverse visions of gender equality, even engaging in struggles over the very word “gender.”

These interviews reflect the scope and complexity of the contemporary Chinese women’s movement. Feminist activists include women leaders from diverse groups, such as Ge Youli, who was involved as a young leader in various urban based organizational activities funded by international donors to disseminate feminist ideas; Zhang Lixi, Vice President of the Chinese Women’s College that affiliates with the All-China Women’s Federation, who has promoted women’s studies in her college; Ai Xiaoming, prominent feminist scholar and activist; and Gao Xiaoxian, who holds an official position in the Shaanxi Women’s Federation while creating several women’s organizations outside the official system to engage in legal services for women, anti-domestic violence movements, and issues of gender and development.

In the second phase, five interviews of a younger cohort of Chinese feminists record the rapidly contracted public space for NGO activism in China since the second decade following the FWCW and severe surveillance by the state over feminist activities initiated by autonomous feminist groups and individuals. They also provide powerful testimonies to tremendous creativity, perseverance and courage demonstrated by young feminists who in many cases are making a precarious living in the private sector without much resource for their feminist activism.

<a href=”https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/globalfeminisms/interviews/china/”>The China site</a> provides videos and transcripts of the interviews (both in Chinese and English). In addition to the interviews, the archive also provides maps, statistics, a timeline, podcasts and other resources to assist understanding of the context in which the activists carried out their work.

Film and Video

Beijing's Petition Village

In China, individuals can complain to higher authorities about corrupt government processes or officials through the petition system. The form of extrajudicial action, also known as "Letters and Visits" (from the Chinese xinfang and shangfang), dates back to the imperial era. If people believe that a judicial case was concluded not in accordance with law or that local government officials illegally violated his rights, they can bring it to authorities in a more elevated level of government for hearing, re-decide it and punish the lower level authorities. Every level and office in the Chinese government has a bureau of “Letters and Visits.” What sets China’s petitioning system apart is that it is a formal procedure—and as Zhao Liang's documentary shows, the system is largely a failure.

A residential area near Beijing South Railway Station was once home to tens of thousands of residents from all over the country. Known as “Petition Village,” its bungalows and shacks were demolished by authorities several times, but many petitioners still clung to the land in search of a clear future. _Beijing Petition Village_ portrays the village in the midst of this upheaval, focusing on the thousands of civilians who travel from the provinces to lodge their complaints in person with the highest petitioning body, the State Bureau of Letters and Visits Calls in the province, only to repeatedly get the brush-off by state officials. Ultimately, in 2007, Petition Village was demolished for good.

The film went on to win the Halekulani Golden Orchid Award for Best Documentary Film at the 29th Hawaii International Film Festival, and a Humanitarian Award for Documentaries at the 34th Hong Kong Film Awards.

Periodicals

The Women's Voice

The Women's Voice (Nüsheng), first issued in Shanghai in October 1932, was a bimonthly magazine published by the Women's Voice Society. It was co-founded by then journalist Wang Yiwei and Liu-Wang Liming, then president of the China Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, with part of the funding coming from the Union, and part being raised by Wang through advertisements and sales.

In the first issue of the journal, the magazine’s mission was described as “to seek liberation for the nation and happiness for all women.” The publication included short commentaries on political affairs, essays, literary works, and readers’ letters. Its content was wide-ranging, including many theoretical articles on the women's movement, discussions on women's participation in politics, marriage freedom, and professional development, reports on the situation of female workers, as well as women's lives in other parts of the world. Although <i>The Women's Voice</i> did not have any political affiliations, it identified with socialism and supported the Chinese Communist Party, believing that national liberation was a prerequisite for women's liberation.

Due to differences of opinion between editor-in-chief Wang Yiwei and president Liu-Wang Liming, the magazine declared its independence and was no longer funded by the China Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in 1934. Due to its left-leaning stance and its sharp criticism of Kuomintang policies, the magazine was subjected to severe censorship and suppression by the KMT authorities and was forced to cease publication in 1935.

After the victory over Japan in August 1945, <i>The Women's Voice</i> resumed publication in November and turned into a monthly magazine. In addition to issuing magazines, the editorial board also held several symposiums, such as “Women's Participation in Politics”, “Women's Education”, and “The Way Forward for Female Intellectuals” The magazine started to collaborate with Liu-Wang Liming again and changed its editorial policy to publish only works by women authors. According to Wang Yiwei, in order to maintain the magazine’s independence, they did not receive any political funding, and that most of its funding came from fundraising events and charity sales. Due to continued harassment by the Kuomintang, Liu-Wang Liming was forced to flee to Hong Kong. Eventually, under both political and financial pressure, <i>The Women's Voice</i> ceased publication in 1947.

<i>The Women's Voice</i> magazine is hosted by the <b><a href="https://mhdb.mh.sinica.edu.tw/magazine/web/index.php"> Modern Women Journal Database</a></b>, operated by the Institute of Modern History of Academia Sinica in Taiwan, and is free for users to register and access. The site contains all of the 1932-1935 issues, but most issues after 1945 were lost, thus only three issues are included. Thanks to the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, for authorizing the CUA to repost.

For more information about the magazine, please see: <a href="http://sites.lsa.umich.edu/wangzheng/wp-content/uploads/sites/948/2024/11/%E7%8E%8B%E4%BC%8A%E8%94%9A-%E6%88%91%E4%B8%8E%E3%80%8A%E5%A5%B3%E5%A3%B0%E3%80%8B-1987.pdf"> Wang Yiwei, “Me and the ‘Women's Voice’: A Tribute to March 8 Women's Day”</a> on the website of Wang Zheng, Professor Emeritus of Women's and Gender Studies and History at the University of Michigan.

Note: In 1942, during the war against Japan, with the financial support of the Japanese and the Wang Jingwei regime , another magazine with the name of <i>The Women's Voice</i> was published in Shanghai, imitating the style and design of the original magazine. The magazine, edited by Japanese left-wing writer and feminist Toshiko Sato (also known as Toshiko Tamura, or Zuo Junzhi in Chinese), was the only women's magazine published in the fallen area of Shanghai under Japanese control. The magazine ceased publication in 1948.

According to research by Tu Xiaohua, an associate professor at the School of Journalism at the Communication University of China, although the magazine had long been regarded as a “traitorous” magazine and a tool of Japanese political propaganda, it also served as a platform for the dissemination of left-wing ideology to a certain extent, due to Toshiko's internationalist stance and the involvement of members of underground CCP members. The magazine is also included in the Modern Women Journals Database.

Periodicals

The Ladies Journal

The Ladies Journal was founded in January 1915 by the Commercial Press Shanghai. It was a monthly magazine primarily targeting upper-class women. It ceased publication in 1932 when the Commercial Press was destroyed by Japanese bombing. The magazine was distributed in major cities in China and overseas, such as Singapore. The magazine was considered an influential forum for the dissemination of feminist discourse in modern China, given its long operation and large readership.

The magazine spanned important historical periods such as the May Fourth Movement and the National Revolutionary period, and readers can see how the political environment and social trends influenced the political stance and style of the publication.

Although it was a women's magazine, the chief editors and the authors of most of the articles were men. According to Wang Zheng, Professor Emeritus of Women's and Gender Studies and History at the University of Michigan, the early articles of The Ladies Journal were more conservative. Although it advocated for women’s education, the goal was to train women to be good wives and mothers. Later, under the influence of New Culture Movement and the May Fourth Student Movement, the magazine was forced to reform itself and began to publish debates on women's emancipation as well as to call for more women's contributions, spread liberal feminist ideas, and support women's movements across the country.

1923 saw the beginning of the National Revolutionary period, and the Chinese Communist Party’s nationalist-Marxist discourse on women’s emancipation started to challenge liberal feminism, and the magazine's influence waned. In September 1925, the magazine ceased to be a cutting edge feminist publication after it changed its chief editor again and shifted its focus to ideas more easily accepted by conservative-minded readers,such as women's artistic tastes.

Although the <i>The Ladies Journal</i> was run by men, and some articles displayed contempt for and discrimination against women, it pointed out and discussed many issues that hindered women's social progress, such as lack of education, employment, economic independence, marriage freedom, sexual freedom, family reform, emancipation of slave girls, abolition of the child bride system, abolition of prostitution, and contraceptive birth control. It was also open to many different ideas and views, all of which were published. It is a valuable historical source for the study of women's studies and modern Chinese history.

Yujiro Murata, a professor at the University of Tokyo, founded the The Ladies Journal Research Society in 2000, along with a number of other colleagues interested in women's history from Japan, Taiwan, China, and Korea. The two main goals of the Society are to produce a general catalog of all seventeen volumes of the Magazine and to bring together scholars from all over the world to conduct studies based on the magazine. With the assistance of the Institute of Modern History of Academia Sinica in Taiwan, the magazine was made into an online repository, which is stored on the Institute’s “Modern History Databases” website, and can be accessed by the public.

Link to the database: https://mhdb.mh.sinica.edu.tw/fnzz/index.php. Thanks to the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, for authorizing the CUA to repost.

图书

A Chronicle of Heroes in Quelling the Turmoil

<i>A Chronicle of Heroes in Quelling the Turmoil—A Collection of Reports on the Deeds of Heroes and Models in Suppressing the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion in Beijing</i> was published by Guangming Daily Publishing House in September 1989. As one of the Chinese Communist Party's official propaganda projects after the suppression of June Fourth, this book collected speeches from a nationwide speaking tour organized by the authorities after the suppression to publicize the "great achievements in quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion." It is one of the texts for studying June Fourth from the official perspective.

图书

One Day Under Martial Law

<i>One Day Under Martial Law</i> was edited by the Cultural Department of the General Political Department of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA), and published and distributed by the PLA Literature and Art Publishing House in October 1989.

The book is divided into two volumes and collects a total of 190 signed articles. Apart from a few police officers from the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau at the time, almost all the authors were soldiers from the PLA martial law troops.

This book is a valuable resource provided by the martial law troops, a special group of witnesses to the June Fourth Tiananmen Incident. The book is a valuable source of information for researchers seeking information on the troops that participated in the June 4th massacre.

This book was also a primary reference for scholar Wu Renhua when he wrote the book <i>The Martial Law Troops in the June Fourth Incident</i>. As an officially organized piece of propaganda material, the book's original intent was to applaud the troops and individual officers and soldiers for what the government described as "quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion." However, because it revealed too much true information, the book was banned shortly after publication. In 1990, the publisher reissued what it called a "selected edition" of the book, which removed over a hundred articles, retaining only 80 signed articles, and the total word count of the book was reduced by more than half. The Archives has collected the original two volumes of <i>One Day Under Martial Law</i>, as well as the “selected edition" that was published after being censored.