Explore the collection

Showing 6 items in the collection

6 items

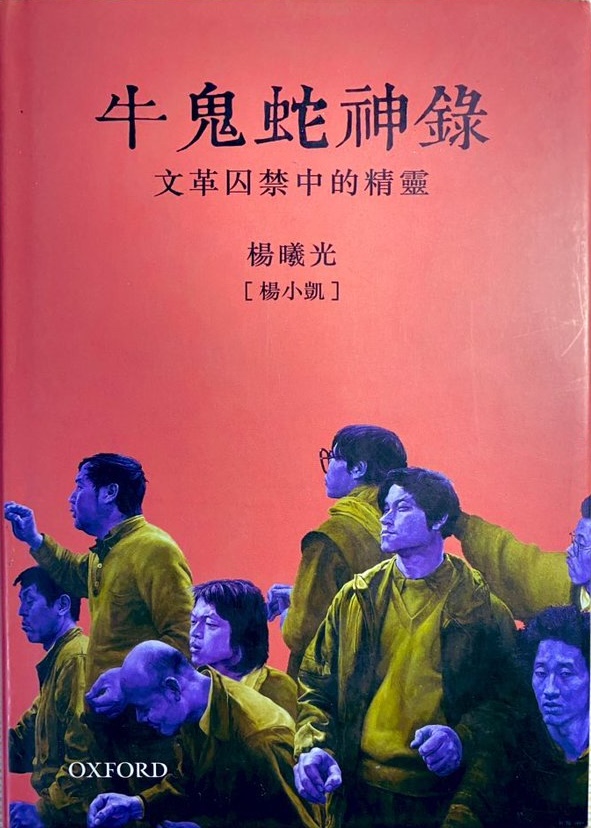

Book

Captive Spirits: Prisoners of the Cultural Revolution

This book is the memoir of Chinese economist's Yang Xiaokai. It tells the stories of more than two dozen characters he met while imprisoned in Changsha during the Cultural Revolution. Published in 1994, it was reprinted in 1997 and 2016. The English version is titled *Captive Spirits: Prisoners of the Cultural Revolution*, published by Stanford University Press in 1997.

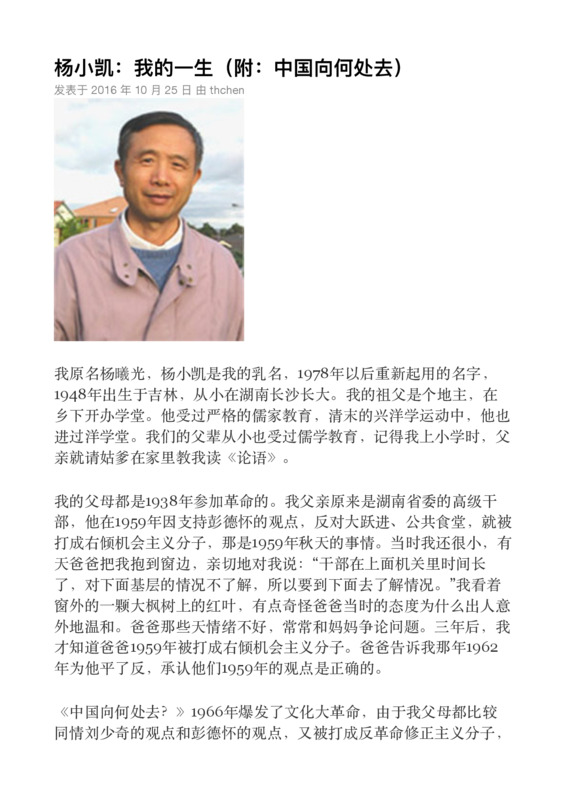

Article

My Life: China's Direction

When the Cultural Revolution broke out, Yang Xiaokai was a senior high school student at No. 1 Middle School in Changsha. On January 12, 1968, he published an article entitled "Where is China Going?" which systematically put forward the ideas of the "ultra-leftist" Red Guards, criticized the privileged bureaucratic class in China, and advocated for the establishment of a Chinese People's Commune based on the principles of the Paris Commune. Yang Xiaokai recalled that his parents were beaten because they sympathized with Liu Shaoqi's and Peng Dehuai's views, and that he was discriminated against at school and could not join the Red Guards. As a result, he joined the rebel faction to oppose the theory of descent. Yang Xiaokai was later sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment for this article. Yang Xiaokai died in 2004. This article is a retrospective of his life.

Article

Poppies under the Red Sun: The Opium Trade and the Yan'an Model

In the 1990s, history scholar Chen Yongfa made a fundamental study of the opium economy two decades before the founding of the CCP and completed a monograph, "Poppies under the Red Sun: The Opium Trade and the Yan'an Model". Since then, more and more research articles have been written on the subject, and new information has appeared. Subsequently, the phenomenon of the opium economy of the CCP's Yan'an regime has also became an important field of study.

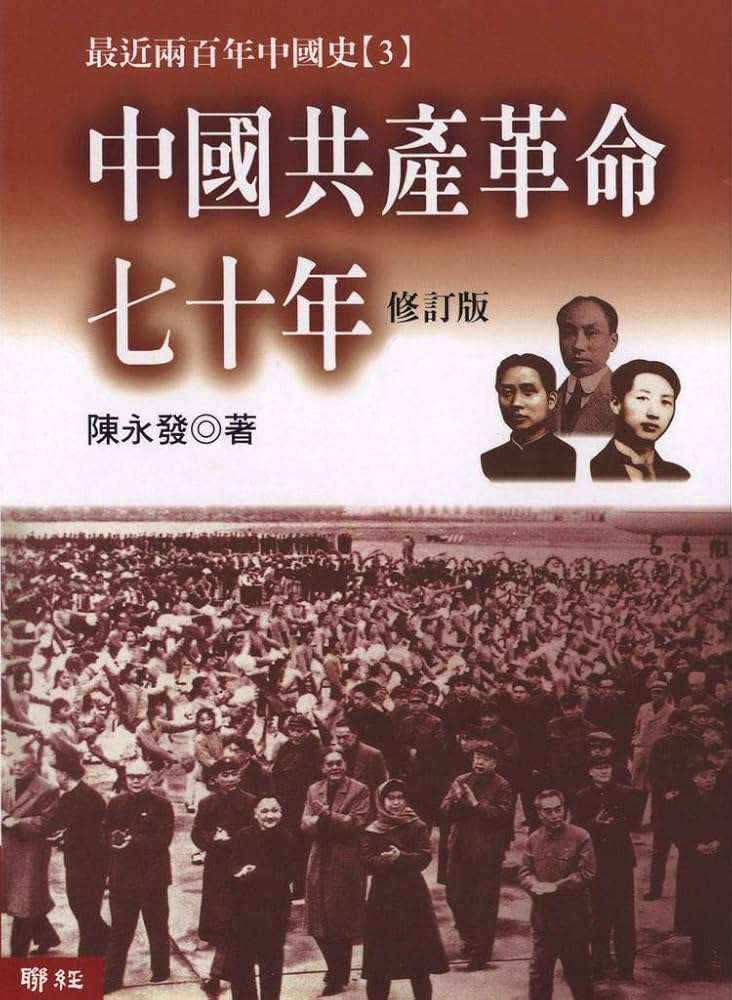

Book

Seventy Years of the Chinese Communist Revolution

Professor Chen Yongfa's book examines the history of the Chinese Communist Party from the perspective of modern Chinese history. It divides it into three stages: revolutionary seizure of power, continuous revolution, and farewell revolution. It delves into three major issues in CCP history: nationalism, grassroots power structure, and ideological transformation and control. published by Taiwan's Linking Publishing in 2001.

图书

The 300,000-Character Letter by Hu Feng

The “300,000-Character Letter,” formally titled “Report on the Practice of Literature and Art Since Liberation,” was a lengthy article submitted by Hu Feng to the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in 1954. This report, approximately 300,000 characters long, thus earned its popular name. It collectively reflected Hu Feng’s views and dissatisfactions regarding the cultural and artistic policies and the state of literature and art since 1949.

The core of the report was Hu Feng’s critique of the prevailing problems in the literary and art circles at the time, such as dogmatism, sectarianism, and formulaic, conceptual approaches. He believed these issues stifled the vitality and creativity of literature and art, hindering their healthy development. In the document, Hu Feng proposed that literary and art workers should have greater creative freedom, emphasizing the subjectivity and authenticity of artistic creation, and arguing that art should not simply be reduced to a tool for political propaganda. He particularly opposed the then-prevalent rigid understanding that “art is subordinate to politics,” advocating that literature and art have their own inherent laws and independent value.

The submission of the “300,000-Character Letter” did not receive a positive response from the Central Committee; instead, it was seen as a challenge to the Party’s literary and artistic line. In 1955, Mao Zedong deemed it to be in opposition to his “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art,” leading to the infamous case of the “Hu Feng Counter-Revolutionary Clique,” where he, along with thousands of others, was accused of forming an “anti-Party clique” and subjected to decades of political persecution. It was not until 1980 that Hu Feng was rehabilitated.

图书

The Memoirs of Hu Feng

The Memoirs of Hu Feng is a work based on the oral accounts of the literary theorist and poet Hu Feng (1902-1985) in his later years, compiled and edited by others. This memoir primarily chronicles Hu Feng’s eventful life, from his early experiences and studies in Japan to his involvement in the left-wing literary movement and his interactions with cultural figures like Lu Xun. It also covers his entanglement in the “Hu Feng Incident” in 1955 and his subsequent decades of political persecution.

The memoir, from a first-person perspective, offers a detailed review of the significant historical events and ideological journey throughout Hu Feng’s life. It not only showcases his dedicated exploration of literary theory and his steadfast adherence to ideas like the “subjective fighting spirit” but also includes a wealth of first-hand materials, such as his correspondence with friends and comrades, and his evaluations of the prevailing literary trends and figures of the time. The book also provides readers with a valuable perspective for understanding the “Hu Feng Incident.”