Explore the collection

Showing 4 items in the collection

4 items

Book

Chen Cheng's Memoirs—The War between the Nationalists and Communists

Mr. Chen Cheng (courtesy name Cixiu; alias Shisou) served as the commander of the KMT army, commander-in-chief of the group army, commander-in-chief of the theater of operations, and chief of the general staff of the KMT. After the defeat of the Kuomintang army in Taiwan, Chen Cheng served the Administrative Yuan as Vice President of the Kuomintang. The volumes associated with *Chen Cheng's Memoirs* were published by Taiwan's National Museum of History in 2005. The series is divided into six volumes: *The Northern Expedition and the Chaos* (one volume), *The War between the Nationalists and Communists* (one volume), *The War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression* (two volumes), and ***The Construction of Taiwan*** (two volumes). The first volume, *The War between the Nationalists and Communists* includes three parts: *Suppressing the Communists - Memories of the Military*, *Summary of Mr. Chen's Words and Actions*, and *Correspondence and Telegrams*. The book has original historical materials related to the five sieges and the counter-insurgency. In particular, this is the first time that important historical materials regarding the correspondence between Chiang Chung-cheng (courtesy name of Chiang Kai-shek) and Cixiu have been made public.

Official Documents

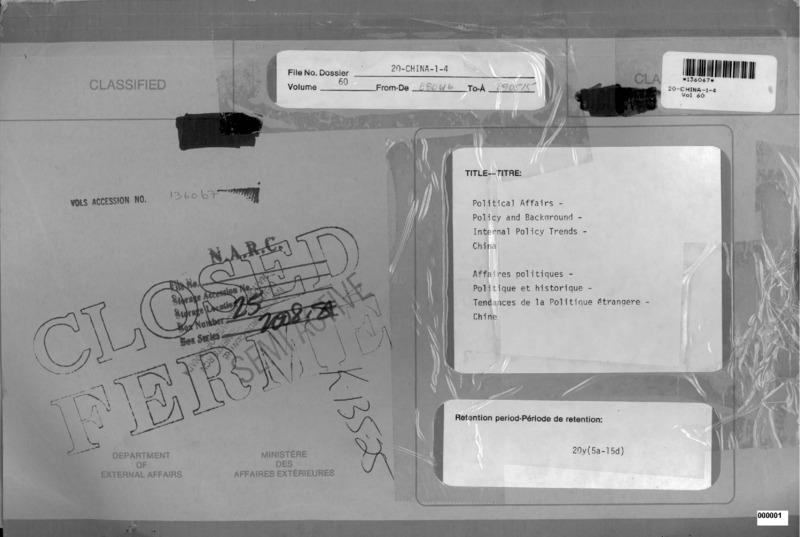

Declassified Files of the Canadian Government on the June Fourth Incident

This document, declassified in January 2015, contains a 1989 diplomatic memorandum from the Canadian Embassy in Beijing. It describes the circumstances surrounding the June 4 massacre as they were known to officials at the Canadian embassy.

The documents, declassified by the National Library and Archives of Canada, show the Canadian government's concern about the invasion of the embassy by Chinese troops. The documents also describe the crackdown in Beijing and how the troops killed citizens.

图书

The 300,000-Character Letter by Hu Feng

The “300,000-Character Letter,” formally titled “Report on the Practice of Literature and Art Since Liberation,” was a lengthy article submitted by Hu Feng to the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party in 1954. This report, approximately 300,000 characters long, thus earned its popular name. It collectively reflected Hu Feng’s views and dissatisfactions regarding the cultural and artistic policies and the state of literature and art since 1949.

The core of the report was Hu Feng’s critique of the prevailing problems in the literary and art circles at the time, such as dogmatism, sectarianism, and formulaic, conceptual approaches. He believed these issues stifled the vitality and creativity of literature and art, hindering their healthy development. In the document, Hu Feng proposed that literary and art workers should have greater creative freedom, emphasizing the subjectivity and authenticity of artistic creation, and arguing that art should not simply be reduced to a tool for political propaganda. He particularly opposed the then-prevalent rigid understanding that “art is subordinate to politics,” advocating that literature and art have their own inherent laws and independent value.

The submission of the “300,000-Character Letter” did not receive a positive response from the Central Committee; instead, it was seen as a challenge to the Party’s literary and artistic line. In 1955, Mao Zedong deemed it to be in opposition to his “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art,” leading to the infamous case of the “Hu Feng Counter-Revolutionary Clique,” where he, along with thousands of others, was accused of forming an “anti-Party clique” and subjected to decades of political persecution. It was not until 1980 that Hu Feng was rehabilitated.

图书

The Memoirs of Hu Feng

The Memoirs of Hu Feng is a work based on the oral accounts of the literary theorist and poet Hu Feng (1902-1985) in his later years, compiled and edited by others. This memoir primarily chronicles Hu Feng’s eventful life, from his early experiences and studies in Japan to his involvement in the left-wing literary movement and his interactions with cultural figures like Lu Xun. It also covers his entanglement in the “Hu Feng Incident” in 1955 and his subsequent decades of political persecution.

The memoir, from a first-person perspective, offers a detailed review of the significant historical events and ideological journey throughout Hu Feng’s life. It not only showcases his dedicated exploration of literary theory and his steadfast adherence to ideas like the “subjective fighting spirit” but also includes a wealth of first-hand materials, such as his correspondence with friends and comrades, and his evaluations of the prevailing literary trends and figures of the time. The book also provides readers with a valuable perspective for understanding the “Hu Feng Incident.”